Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide

Related Articles: Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction

With enthusiasm, let’s navigate through the intriguing topic related to Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide. Let’s weave interesting information and offer fresh perspectives to the readers.

Table of Content

- 1 Related Articles: Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide

- 3.1 Understanding the Foundation: The Core Components of Concept Mapping

- 3.2 Navigating the Styles: A Comprehensive Overview

- 3.3 Beyond Styles: The Importance of Customization and Context

- 3.4 Addressing Common Queries: FAQs on Concept Mapping Styles

- 3.5 Tips for Effective Concept Mapping: A Guide to Optimizing the Process

- 3.6 Conclusion: Embracing the Power of Visual Representation

- 4 Closure

Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide

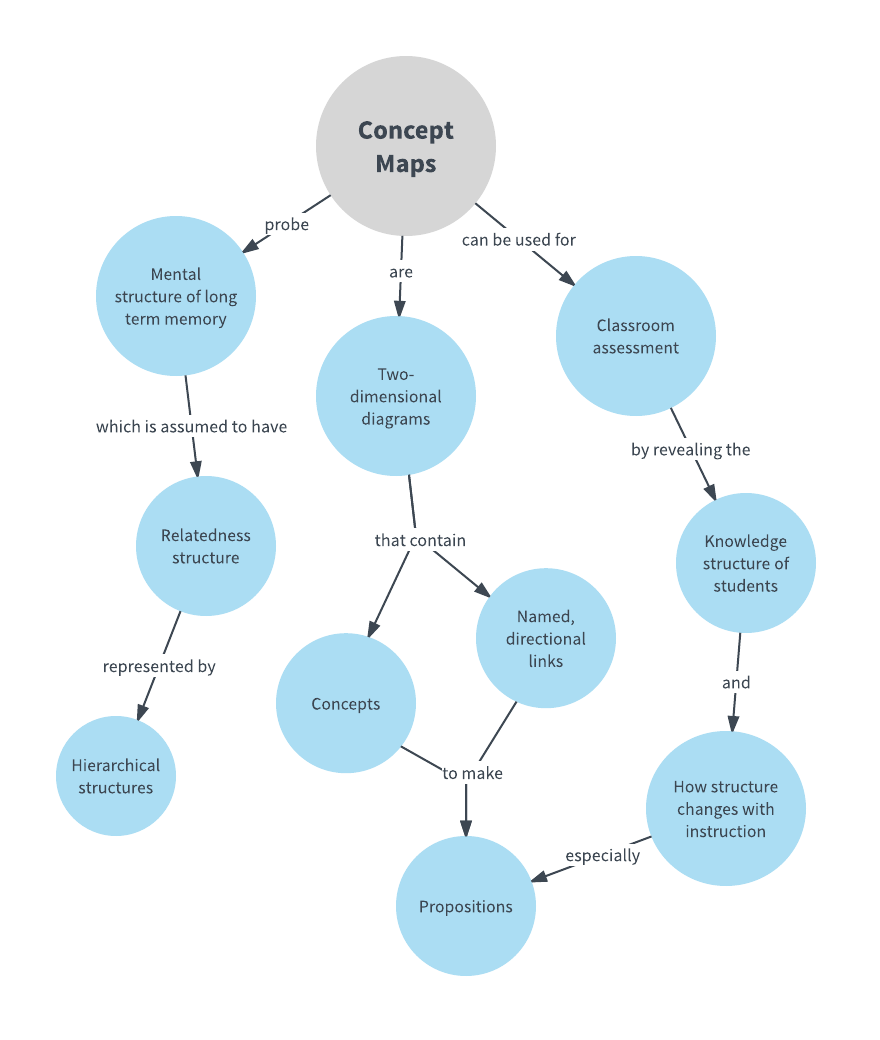

Concept mapping, a visual representation of knowledge, has proven its efficacy in various domains, from education and research to business and personal development. This technique employs a network of nodes and connecting lines to depict relationships between concepts, fostering a deeper understanding and facilitating knowledge retention. While the fundamental principle of connecting ideas remains constant, the diverse approaches to concept mapping, known as styles, offer unique advantages depending on the specific application and user preference. This exploration delves into the nuances of various concept mapping styles, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and practical applications.

Understanding the Foundation: The Core Components of Concept Mapping

Before delving into specific styles, it’s crucial to understand the fundamental elements that underpin all concept mapping techniques:

- Nodes: These represent individual concepts or ideas, typically enclosed in shapes like circles, squares, or rectangles.

- Links: Lines connecting nodes, signifying relationships between concepts. These relationships can be hierarchical, associative, or causal, denoted by different types of lines, arrows, or labels.

- Propositions: Statements expressing the relationships between concepts, often written alongside the connecting links.

- Hierarchy: The organization of concepts into a structured hierarchy, with more general concepts at the top and specific ones branching out below.

Navigating the Styles: A Comprehensive Overview

The diverse styles of concept mapping cater to different learning preferences and application contexts. Here’s a detailed exploration of prominent styles:

1. Hierarchical Mapping:

- Characteristics: This style emphasizes the hierarchical organization of concepts, with a central, overarching concept at the top, branching out into progressively more specific sub-concepts. This structure resembles a tree, with the main concept as the trunk and sub-concepts as branches.

- Strengths: Ideal for organizing information in a clear, structured manner, particularly for complex topics with well-defined hierarchies. It effectively facilitates understanding of relationships between concepts and promotes a systematic approach to knowledge acquisition.

- Limitations: May not be suitable for representing complex relationships that are not strictly hierarchical. The linear structure can limit the exploration of diverse connections and perspectives.

- Applications: Effective for organizing information for presentations, research papers, and textbooks. Ideal for teaching and learning subjects with a clear hierarchical structure, such as biology, history, or computer science.

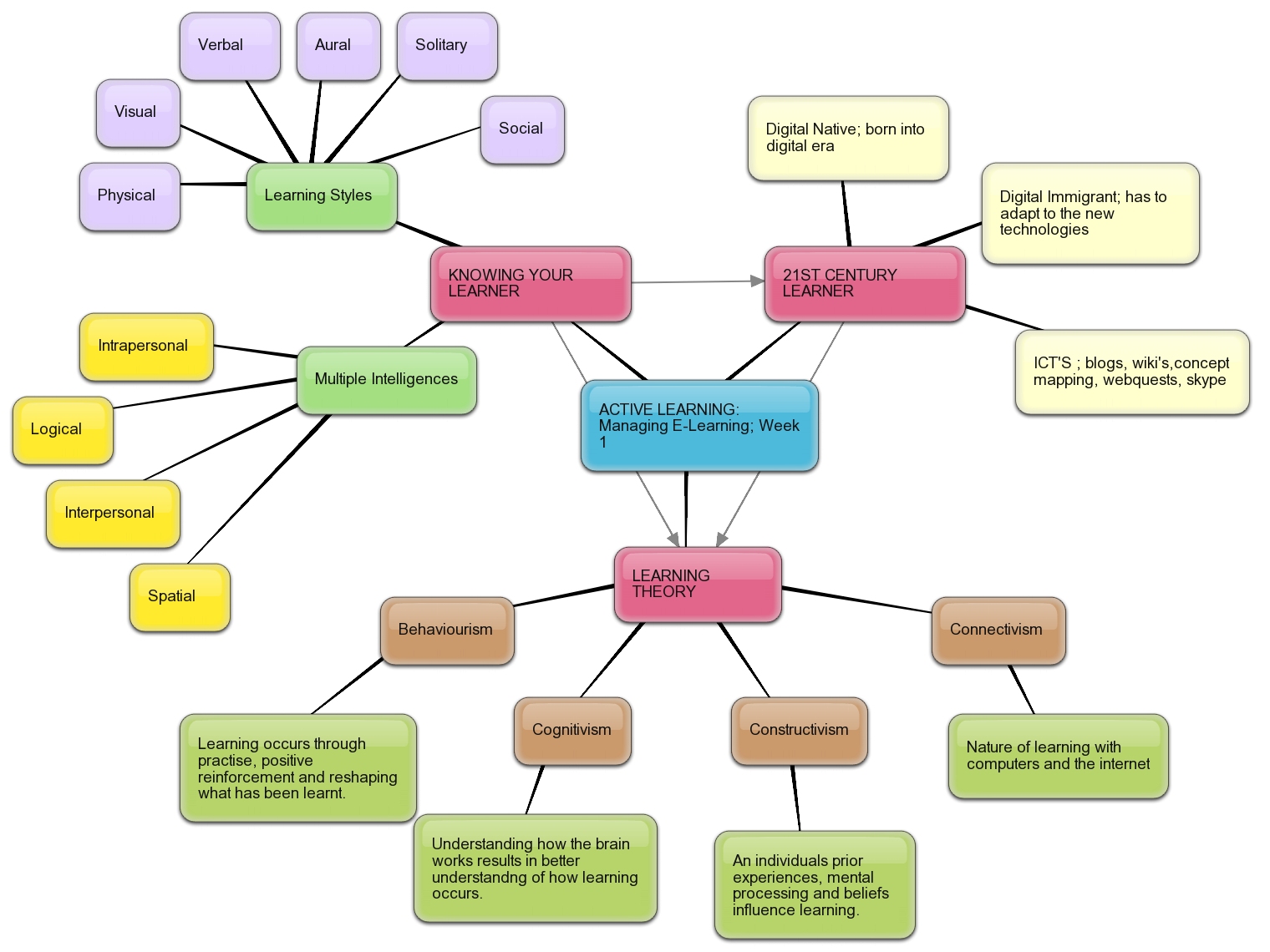

2. Spider Mapping:

- Characteristics: This style, also known as mind mapping, uses a central concept as the hub, with radiating branches representing associated ideas. These branches can further sub-divide into sub-branches, creating a web-like structure.

- Strengths: Encourages creative brainstorming and free-flowing idea generation, allowing for exploration of multiple connections and perspectives. Its radial structure promotes visual clarity and facilitates the identification of key themes.

- Limitations: Can become visually complex with a large number of concepts, potentially hindering clarity and organization. The lack of strict hierarchy can make it challenging to identify specific relationships between concepts.

- Applications: Ideal for brainstorming, note-taking, and problem-solving. Particularly useful for exploring complex topics with numerous interconnected ideas, such as creative writing, project planning, and problem-solving in business.

3. Flowchart Mapping:

- Characteristics: This style focuses on depicting the sequential flow of processes or steps. It utilizes shapes and arrows to represent actions, decisions, and outcomes, illustrating the progression of a process.

- Strengths: Effectively visualizes the steps involved in a process, promoting clarity and understanding. It facilitates the identification of potential bottlenecks and areas for improvement, making it valuable for process analysis and optimization.

- Limitations: Primarily suited for visualizing linear processes, potentially limiting its applicability for representing complex, non-linear systems.

- Applications: Widely used in engineering, software development, and business process analysis. Effective for creating instructional materials, presenting algorithms, and documenting workflows.

4. Fishbone Mapping:

- Characteristics: This style, also known as Ishikawa diagram, focuses on identifying the root causes of a problem or issue. It uses a central spine representing the problem, with branches emanating from it representing potential causes categorized into categories like people, process, materials, environment, and equipment.

- Strengths: Facilitates systematic problem analysis and identification of root causes. It encourages collaborative brainstorming and encourages a holistic perspective on problem-solving.

- Limitations: May not be suitable for exploring complex relationships or representing abstract concepts. The focus on identifying causes might limit its applicability for understanding broader contexts.

- Applications: Primarily used in quality management, problem-solving, and root cause analysis. It’s effective for identifying and addressing issues in manufacturing, service delivery, and various other industries.

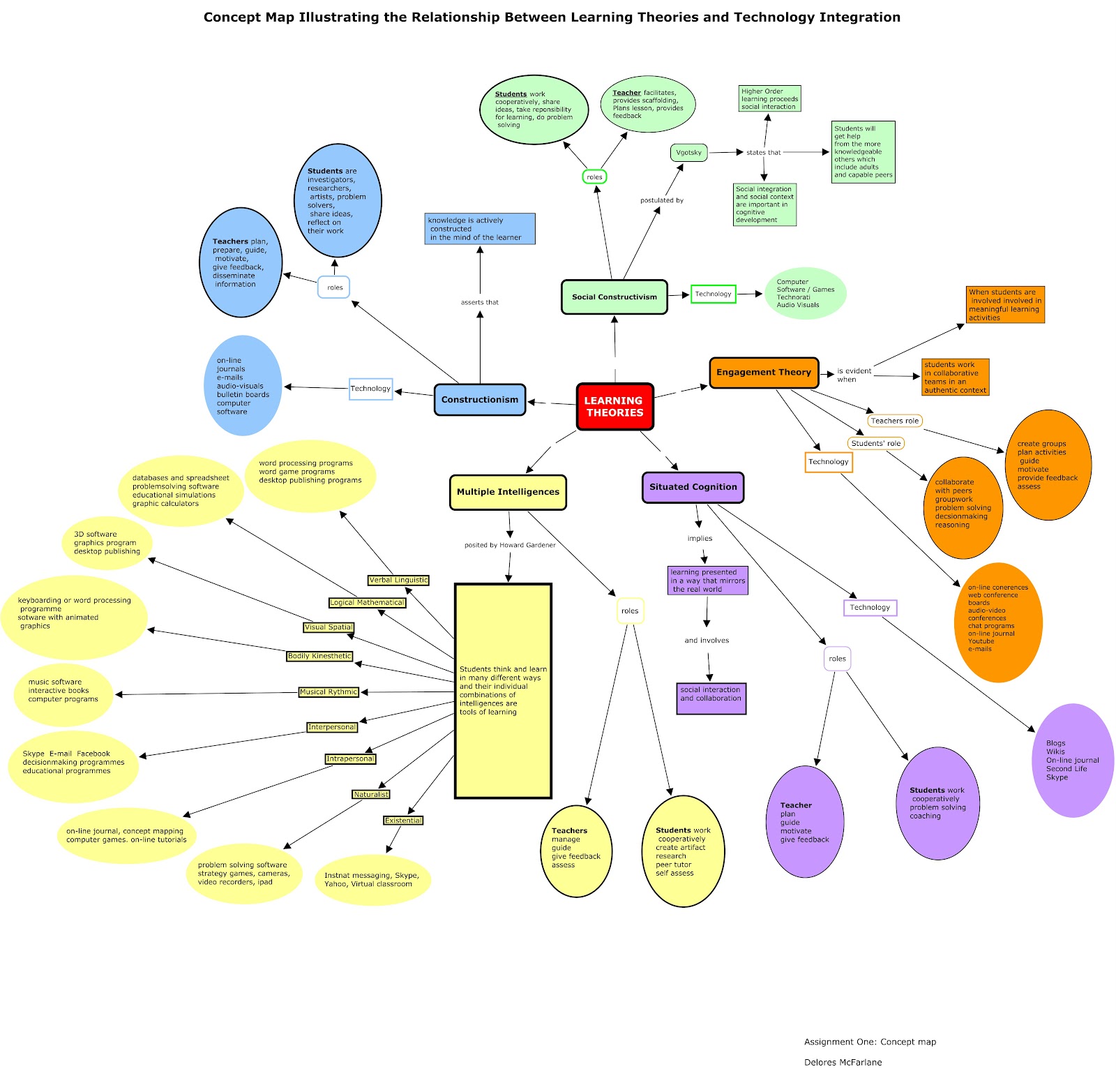

5. Network Mapping:

- Characteristics: This style emphasizes the interconnectedness of concepts, showcasing the complex relationships between them. It allows for the representation of multiple connections and perspectives, creating a rich network of information.

- Strengths: Offers a comprehensive view of the relationships between concepts, promoting a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of knowledge. It encourages exploration of diverse perspectives and fosters creative thinking.

- Limitations: Can become visually complex with a large number of concepts, potentially hindering clarity and understanding. The lack of a clear hierarchy can make it challenging to navigate and interpret.

- Applications: Suitable for representing complex systems, such as social networks, ecosystems, or knowledge domains. It can be used for research, project management, and strategic planning.

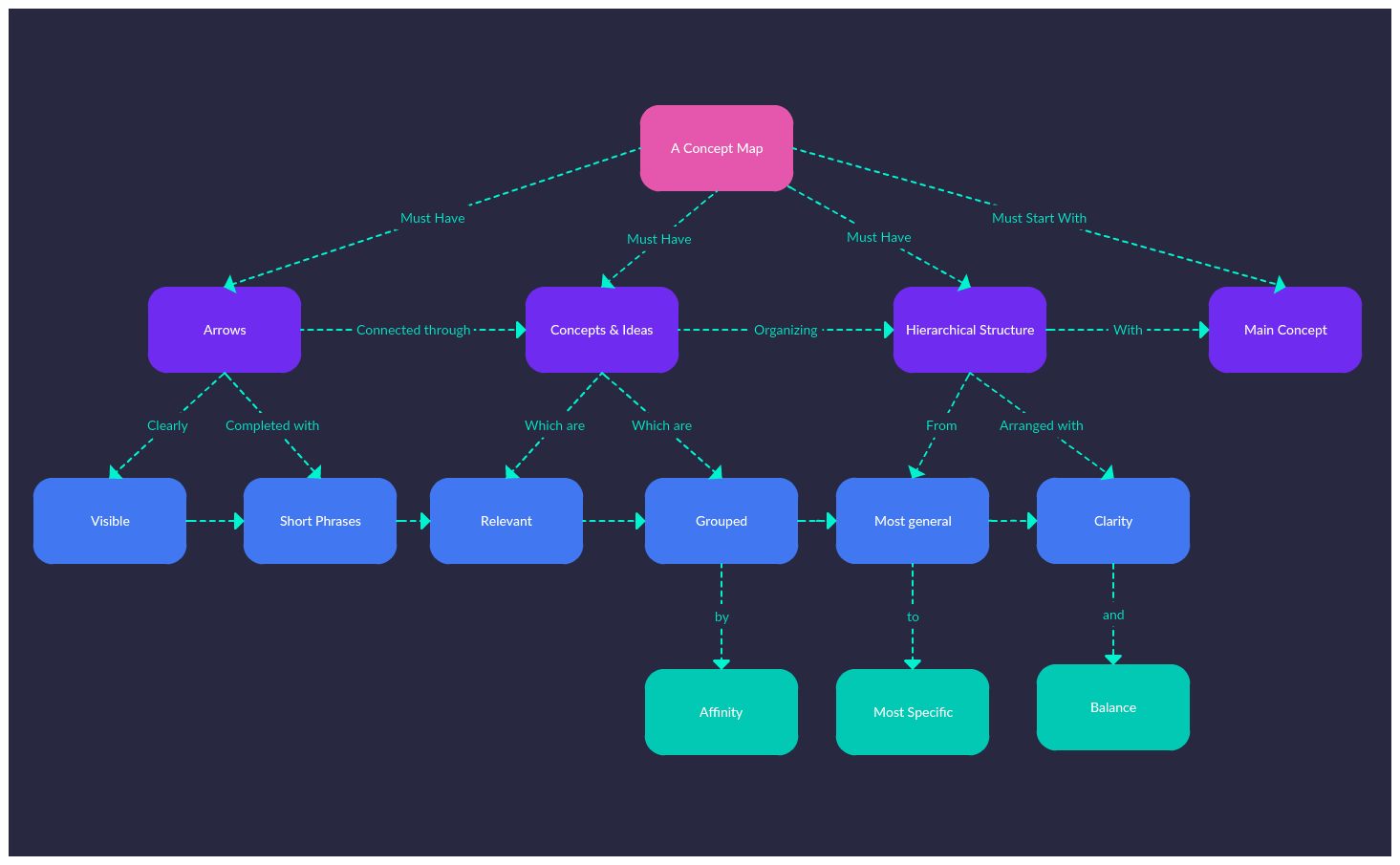

6. Concept Mapping for Concept Mapping:

- Characteristics: This meta-mapping approach uses concept mapping to represent the concept mapping process itself. It helps to understand the underlying principles and techniques involved in creating effective concept maps.

- Strengths: Provides a framework for understanding the process of concept mapping, facilitating the development of effective mapping strategies. It encourages reflection on the strengths and limitations of different styles and promotes the development of individual mapping preferences.

- Limitations: May be less directly applicable to specific content areas compared to other styles. The focus on the process might not be immediately relevant to all users.

- Applications: Primarily used for pedagogical purposes, helping students and educators understand the theoretical underpinnings of concept mapping. It can also be used for self-reflection and improvement of individual mapping skills.

Beyond Styles: The Importance of Customization and Context

While the diverse styles offer valuable frameworks, it’s crucial to recognize that concept mapping is a dynamic and flexible tool. Effective utilization often involves customizing the chosen style to suit the specific context and purpose. This customization may involve:

- Adapting the visual representation: Utilizing different shapes, colors, and fonts to highlight specific concepts or relationships.

- Adding annotations and explanations: Incorporating brief descriptions, definitions, or examples to enhance understanding.

- Combining multiple styles: Integrating elements from different styles to leverage their unique strengths and address the specific needs of the task.

Ultimately, the choice of style and the level of customization depend on the individual’s goals, the complexity of the subject matter, and the intended audience.

Addressing Common Queries: FAQs on Concept Mapping Styles

1. Which style is best for a particular topic?

The optimal style depends on the specific topic and the desired outcome. Hierarchical mapping is suitable for structured information, spider mapping for brainstorming, flowchart mapping for processes, and fishbone mapping for problem analysis. Network mapping is best for complex interconnected concepts.

2. Can I combine different styles?

Yes, combining styles is encouraged to leverage their strengths and address specific needs. For instance, a hierarchical map can be augmented with spider mapping branches for exploring sub-concepts.

3. How do I choose the right style for my needs?

Consider the purpose of the map, the complexity of the topic, and your personal preferences. Experiment with different styles to identify the most effective approach for your specific context.

4. What tools can I use for concept mapping?

Various digital and analog tools are available. Digital tools like MindNode, XMind, and Miro offer interactive features and collaboration capabilities. Analog tools include whiteboards, sticky notes, and pen and paper.

5. How can I improve my concept mapping skills?

Practice is key. Start with simple topics, gradually increasing complexity. Experiment with different styles and techniques. Seek feedback from others and reflect on your mapping process.

Tips for Effective Concept Mapping: A Guide to Optimizing the Process

- Start with a clear objective: Define the purpose of the map to guide the selection of style and focus.

- Identify key concepts: Brainstorm and list the essential ideas related to the topic.

- Establish relationships: Analyze the connections between concepts and determine their nature (hierarchical, associative, causal).

- Use visual cues: Employ shapes, colors, and fonts to highlight important concepts and relationships.

- Keep it concise and clear: Avoid overloading the map with too much information. Use brief labels and concise descriptions.

- Iterate and refine: Don’t be afraid to revise and adjust your map as you gain a deeper understanding of the topic.

Conclusion: Embracing the Power of Visual Representation

Concept mapping, with its diverse styles and adaptable nature, provides a powerful tool for organizing knowledge, facilitating understanding, and promoting creative thinking. By embracing the principles of visual representation, individuals can unlock the potential of concept mapping to enhance learning, problem-solving, and communication across various disciplines and domains. The choice of style and the level of customization ultimately depend on the specific context and individual preferences, allowing for a personalized approach to knowledge exploration and effective communication.

Closure

Thus, we hope this article has provided valuable insights into Exploring the Landscape of Concept Mapping Styles: A Comprehensive Guide. We thank you for taking the time to read this article. See you in our next article!